by Jenna | Oct 2, 2013 | Writing Articles

In the third and final session of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "Bridging the Gap from Motivation to Structure With the Enneagram." Today's post is a recap of what we discussed.

In the third and final session of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "Bridging the Gap from Motivation to Structure With the Enneagram." Today's post is a recap of what we discussed.

His process for "bridging the gap" from premise line to character to story is quite fascinating, and he illustrated it using a breakdown of The Great Gatsby according to the Enneagram.

Bridging the gap

Here's an overview of the process:

- Step 1. Write out your premise line and log line.

(See the last post for more on premise line development.)

- Step 2. Define the moral problem that best illustrates the story's premise line.

(In Gatsby, Nick focuses on trying to fit in and be liked, he isn't being his truest self, which is a form of lying.)

- Step 3. Look for the Enneagram type that best represents the motivations (not behaviors) of someone with that moral shortfall.

(Nick most aligns with the Enneagram type 9.)

- Step 4. Study the integration and disintegration points for that type to identify what the character is capable of and what they're greatest opponent might be.

(Points 3 and 6, respectively.)

- Step 5. Explore the entertaining moral argument possibilities between those two types.

(Can you succeed and achieve without giving up your soul?)

- Step 6. Brainstorm about the communication styles, "pinches", and blind spots of each of those two types.

(Nick has various challenges that Gatsby can poke at and wreak havoc with.)

- Step 7. Map your story using these Enneagram components and correlate them with the visible structure components we discussed last time.

(This includes the protagonist, moral problem, chain of desire, focal relationship, opposition, plot & momentum (midpoint complication, low point, and final conflict), and evolution/de-evolution and is the more complex step where the story is broken down into a greater level of detail).

Your turn

Have you considered using the Enneagram in your story development? Will you consider using it in the future? We'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Warmly,

You may also be interested in:

Image by © Royalty-Free/Corbis

by Jenna | Oct 1, 2013 | Writing Articles

In the second class of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "The Critical Importance of Premise Line Development." Today's post is a recap of what we learned.

In the second class of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "The Critical Importance of Premise Line Development." Today's post is a recap of what we learned.

Jeff started off by talking about the importance of being clear about what you're writing is about a situation or a story:

- A story is about a person on a journey of change, where they are trying to achieve a goal or attain a desire and have a revelation about themselves at the end. Stories include relationships, because, as Jeff says, "Stories are conversations, not monologues."

- A situation, on the other hand, is usually some kind of problem or predicament with a solution that tests a protagonist's problem-solving skills but doesn't reveal character. Few, if any, subplots, twists, or complications are required to solve the problem, and it ends in the same emotional emotional space it began in. Standard genre beats may still evident but not the deeper underpinnings of story structure.

While Jeff doesn't suggest that story is better than situation or vice versa, he says that they require different building blocks to successfully deliver them. A story will rely on deeper story structure components, while a situation will rely on entertainment value, great set pieces, and good dialogue, but won't reveal character or be driven by a moral problem or theme.

And what is story structure?

Jeff defines story structure differently than the way most of us have learned to think of it. Most of us think of things like inciting incidents, turning points, mid-points, climaxes, and resolutions as story structure. Jeff describes these as "story beats" and says that most writing systems that purport to be about structure are actually focused on these typical beats and are missing the deeper, natural structure implied by both premise development and character motivation.

Getting from idea to premise line

When a story idea first arrives, it often comes as an "undifferentiated mass". It's a collection of swirling notions and intuitive instincts that don't translate yet into a clear organized story structure.

Jeff uses premise line development as a tool to begin to decipher the fuzzy, abstract ideas into a more concrete, contained story -- the nascent beginnings of story structure. He compares it to stepping down electricity from the power plant into a useable form in a residential setting. It has to go through transformers to make it available at a functional level. The premise line is the first step in translating from that vague mass of ideas into something resembling a story.

The way that he does this is by using seven core elements to begin to tease out the components of the story and shape them, including:

- Character -- do you have a sense of a character who will be central to the story?

- Constriction -- what happens that pushes the character off the line they're on at the beginning of the story?

- Desire -- what does this character want? At this point, we're not talking about something specific or tangible, that comes later, but rather a sense of a core desire or motivating force.

- Relationship -- who is this character in relationship with? (Again, stories are conversations.)

- Resistance -- what is the push back or opposition that stops the main character from getting what they want?

- Adventure and/or Chaos -- what is the adventure or chaotic experience the character has that leads them to the epiphany at the end?

- Change -- this is the dramatic epiphany the end -- how the character changes as a result of their experiences.

Moving from premise line to visible structure

Once you've identified your premise line, you can then move to a more "visible structure" for the story. This is a process of taking what you've started with and beginning to develop and flesh out the pieces of the story more deliberately. At this stage of the process, you'll make the following shifts:

- The character becomes the protagonist.

- The constriction becomes the moral problem of the protagonist. (This informs the inciting incident.)

- The character's desire becomes a chain of desire (a sequence of goals or desires all related back to the character's core desire).

- The relationship becomes the focal relationship for the story, the person the protagonist experiences the journey with.

- The resistance becomes the central opposition. At the outset and premise level, you may just have a sense of an opposing force. At this stage it would become personal, dramatic, and/or personified.

- The adventure/chaos becomes the plot and momentum of the story through the second act. (This is the part of the story that includes the typical story beats, like midpoint, low point, and climax).

- The change is the evolution or de-evolution of the protagonist.

Bridging the gap using the Enneagram

In order to make the transition from that undifferentiated mass of the original idea to the more visible structure of the premise line all the way into a visible, clear structure, Jeff uses the Enneagram to help identify the specifics for each one of these elements, such as:

- The best protagonist for the story, based on the personal change the story is designed to illustrate.

- The best opposition or antagonist for the story, designed to help provoke the protagonist into that change.

- Brainstorming and understanding the protagonist's core desire based on their Enneagram type, to design a chain of desires that the character seeks that drives the story forward.

- The best allies or focal relationships for the protagonist.

- The best likely inciting incidents, turning points, midpoints, low points, and battles/climaxes that will stimulate your specific character and/or be driven by him/her to the final outcome of the story.

The Enneagram doesn't tell us the ONLY options for each of these, but rather suggests the best form for each of these elements. Then as the writer, it's up to you to begin to craft the specific story details to deliver that. (Form follow function, after all.)

For instance, at the broadest level, an Enneagram Three seeks approval from the outside as a way of validating themselves, but what they really need is to have their own sense of value and sense of self. So a story about a Three would be designed to play out that journey in a visual, visible metaphor organized around the ideas of approval-seeking as the constriction, taking an action that would cause a loss or challenge based on that approval-seeking as an inciting incident, to a low point where the Three finally realizes they are sacrificing themselves on the altar of approval and giving up everything to do so, all the way to a climactic moment where the Three stops looking outside themselves for approval and decides to find it within.

At a more specific level of story detail, those ideas could play out with a businessman who will never say no to a contract, trying to please everyone and perform by juggling and obfuscation, but he finally says yes to too many projects and the house of cards he's built around himself comes crashing down. He would then realize he needs to choose projects and work that HE values, and by so doing, recognize his OWN inherent value. It's HIM that makes the projects successful, not the game he's playing.

And of course, we can get even more specific from there, as well as fleshing out the details of his supporting relationships and opposition.

You may also be interested in:

by Jenna | Sep 18, 2013 | Writing Articles

In the first class of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "The Secrets of the Enneagram Most Writers Are Overlooking." We had a mix of participants on the line, it seemed to be about 50-50 on who had prior experience or knowledge of the Enneagram and who did not, and Jeff did a great job of making the material accessible to everyone. Today's post is a recap of what we learned.

In the first class of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "The Secrets of the Enneagram Most Writers Are Overlooking." We had a mix of participants on the line, it seemed to be about 50-50 on who had prior experience or knowledge of the Enneagram and who did not, and Jeff did a great job of making the material accessible to everyone. Today's post is a recap of what we learned.

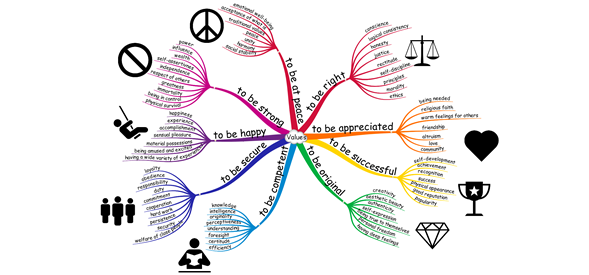

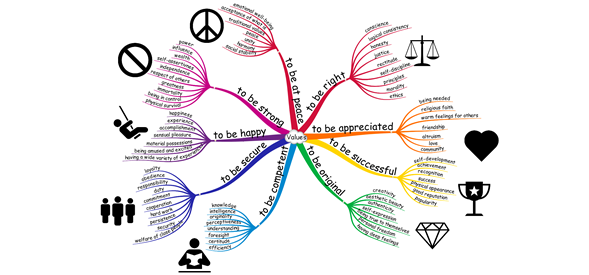

Jeff talked about how powerful the Enneagram can be for writers because of its archetypal patterning of human drives and behaviors that transcend cultural boundaries.

He walked us through a quick overview of each of the nine Enneagram types, or styles, as he calls them. He describes the styles as being nine basic strategies for living, including showing us how we behave when we feel successful, weak, vulnerable, and strong. His descriptions of the types quickly demonstrated how powerfully the Enneagram types can be used for character development and why so many writers have used the Enneagram that way for so long. He also described several ways writers can use the Enneagram beyond simple character development, which I'll give you the highlights of in a moment.

The Nine Core Enneagram Styles

To start, though, let's take a look at the nine core Enneagram styles:

- The One is the "do the right thing" person who derives their sense of safety, security, and love in the world by following the rules and doing things perfectly.

- The Two is the "to be loved" style, sometimes called "the caretaker". Twos look for the person with the most power in their environment and make themselves indispensable to that person in order to feel loved. They manipulate in order to get the love they want. Glenn Close's character in Fatal Attraction is an example of an extremely unhealthy or "disintegrated" Two.

- The Three is the "performer or achiever" and focuses on getting EVERYONE's approval (not just one person in power, like the Two). Jeff described the Three as a "therapist's nightmare", because they tend to perform emotion rather than feel it (though they do have and feel emotions deeper down).

- The Four is the "to be special" style. This type has a negative side, feeling that something is missing. They can be melancholy, depressed, and always looking for someone to help them solve the problem of "what's missing". They "long to long" and are often overly self-oriented.

- The Five is the "thinker" type who controls their environment by controlling information. They don't like intense emotions and control the people around them by controlling (sometimes withholding) information. Keanu Reeve's character "Neo" in The Matrix is a great example of a Five who controls his world through data, at the beginning of the story in particular.

- The Six is the "safety-security" style. Sixes always have a plan, they know where the pot holes and the landmines are. They tend to have a problem with trust, but if you win their loyalty, they'll be a friend forever. If their lives are working, they tend to be happy, but they will also dismantle their entire lives in order to have a problem to solve. There are also "counter-phobic" sixes who tend to strike first if they think you might be a threat to them.

- The Seven is the "to have fun" style. "Why have one friend when you can have 100 friends?", as Jeff said. Sevens are great at having fun and enjoying life, but they also have a tendency to be addictive types and their fast-paced, highly-active lifestyles are designed to help them avoid their inner pain.

- The Eight is the "self-reliant / leader" style. They control people by making the rules. They are the most projected on than any other Enneagram type, because they have such a strong presence that can feel confronting. They can be very protective of the downtrodden and provide leadership or can become dictators at an extreme. They avoid relying on other people.

- The Nine is the "peacemaker", the one who finds safety by finding common ground. Nines make sure that everyone is heard except themselves -- they are self-abandoning. They don't get in trouble, but they are also not seen.

Character Development & Beyond

Here are some story development applications Jeff described for the Enneagram:

- Determining your characters' core personality types -- this has been done by writers for years.

- Determining your protagonist's growth arc -- Each of the nine types has a specific drive toward "disintegration" and a higher place within them for "integration". Studying those paths of disintegration and integration can help writers get clearer about their characters' growth arcs in their stories. This has also been done for years by writers.

- Choosing the best protagonist for your story, depending on the moral problem you want your character to solve in the story and the type of story you are telling. For example, love stories are often Two-driven stories, and pure sci-fi stories are often Five-driven stories.

- Selecting the best opponent for your protagonist, based on your protagonist's Enneagram type and growth arc, so they are designed for maximum conflict that will provoke the protagonist's growth.

- Choosing the best allies for your protagonist, so your characters interplay with each other for best effect.

- Designing and structuring your story to naturally take your protagonist through exactly the right crucible that forces them to move from their moral problem into their point of integration, or revelation, by the end of the story.

- Understanding the types of stories we will be innately drawn to tell, based on our own Enneagram styles, which can make us more conscious writers.

All of these help us "pre-structure" our stories BEFORE we go into story beat development, which is what so many of us are familiar with already and tend to think of as story structure (like Blake Synder's Save The Cat method, for instance).

Next week, in the second class of our series, Jeff will be talking to us about:

- Premise line development and its critical importance in story development.

- Story structure components.

- How to tell the difference between whether or not you have a story or a situation.

Your turn

Are you familiar with the Enneagram? What has it helped you shift or change in your own life? If you're a writer, do you use it in your writing? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Warmly,

You may also be interested in:

Graphic courtesy of

by Jenna | Sep 12, 2013 | Writing Articles

I've been a follower of the Enneagram since 1998. The Enneagram is a powerful system that is highly useful for understanding your personality and inner motivations.

My work colleague told me about it one day, and mentioned that she was pretty sure I was a "Six" just like she was. Horrified to be lumped into a category with someone I often struggled to get along with, I quickly set out to prove that I WASN'T A SIX! I didn't care what it actually was, I just didn't want to be THAT.

I took a few tests online and found that the results were mixed. In some I WAS a Six. The horror! In others, it came back as a Four. Hmm. (The tests can be a great place to start if you're curious about this.)

My colleague suggested that the best way to "get" the Enneagram was to attend a panel discussion, where I could watch and hear from groups of particular types. I think over the years I've now attended two different Enneagram panel series and one other Enneagram class here in the local San Francisco Bay Area.

But what I vividly remember is watching the panel of Fours in the first series I attended. I was already suspecting I was a Four -- the Individualist, the Dreamer, the Romantic, the Tragic Romantic, the Artist -- and I was determined to find out once and for all. (The names vary depending on whose book you're reading, and some people don't even like to use the names at all because of the projections people make onto them.)

Fours are known for wanting to be different and special. Unique. It's both a source of pain and pride for them.

At that first panel series, I watched the entire row of Fours talk about their experiences being a Four. We got all the way down to the very end of the line (there must have been 12 to 14 people easily), and the last woman said, "I don't know, I just don't really identify with everyone else here. I mean, I know I'm a Four, and I know you all are too, but I just feel different."

Right then, I knew in my core, as she expressed EXACTLY WHAT I WAS THINKING, that I was, in fact, a Four.

It wasn't exactly a thrilling revelation, though it certainly did alleviate my other drama about my colleague (Fours seem to, ahem, like, create, and attract drama). Mostly it hit me: "Oh man, you mean all that stuff that Fours are? I'm that too??"

Most of the Enneagram books out there tend to look at each of the nine types from a fairly negative perspective, and a lot of people can be overwhelmed by that. I quickly learned that most of Helen Palmer's books were too dark for me, and found Personality Types: Using the Enneagram for Self-Discovery* by Don Richard Riso with Russ Hudson. I loved the levels of integration and disintegration they described because it gave me a sense that there was hope for improvement and it helped me learn a ton about myself and my suddenly transparent behavior and fixations.

Most of the Enneagram books out there tend to look at each of the nine types from a fairly negative perspective, and a lot of people can be overwhelmed by that. I quickly learned that most of Helen Palmer's books were too dark for me, and found Personality Types: Using the Enneagram for Self-Discovery* by Don Richard Riso with Russ Hudson. I loved the levels of integration and disintegration they described because it gave me a sense that there was hope for improvement and it helped me learn a ton about myself and my suddenly transparent behavior and fixations.

So fast-forward a few years.

Over time, the Enneagram has been a great tool for me for both understanding and getting along with my Nine husband (a Peacemaker) and helping my clients understand themselves better (of course many of them tend to be Fours :) ). One of my colleagues has written a series of books for empaths based around the core Enneagram principles* that I highly recommend. I've written a few articles related to the Enneagram myself, and have a page on my old website about the Enneagram and how it relates to high sensitivity.

And once I started writing fiction, I turned to the Enneagram to use it to develop my characters. But I thought of it as simply that, a tool to help me develop each character individually.

I never really thought of it as anything more, or how the characters might be related to each other through the Enneagram.

Then last October, I was following one of my fellow ScriptMag columnists online, Jeff Lyons, who tweeted something about a class he was offering and I discovered that he also offered writing-related, "rapid story development" Enneagram classes and I was enthralled! I wanted to know more right away. It didn't take long for us to talk about him coming here to Berkeley to teach his method.

What amazes me most about it is that he uses a combination of story premise and the archetypal Enneagram system to do story structure work. Not just character, not just motivation, not even just how characters are related. He works with his own proprietary story premise model with the Enneagram to tackle character, plot, and structure in a holistic, integrated fashion.

Who knew!?

I can't wait to see how he does it, and I hope you'll consider coming to join us too. He's going to be teaching the Enneagram in a very hands-on fashion -- it sounds like perfect hybrid of observation, teaching, taking action, and getting a chance to put it into practice. He's even going to do some 1:1 "magic time" with a few lucky participants on their own story structure and premise. It's going to be amazing.

If you can't come and be there live, or if you want more information, we'd love to have you join us over the next three weeks for a three-part interview series with Jeff so you can get a sense of this ground-breaking tool. You can find out more about the teleclass series and register here.

Your turn

Are you familiar with the Enneagram? What has it helped you shift or change in your own life? If you're a writer, do you use it in your writing? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Warmly,

You may also be interested in:

by Jenna | Sep 4, 2013 | Writing Articles

One of the cleverest smokescreens in writing is creative apathy.

This is the point with a project where you suddenly get bored or lose interest in your writing. It tends to crop up at key stages in your writing project, like midway through or even just shy of the end.

When you hit it, you’ll start thinking maybe you’re just not that interested in this project and maybe it’s time to move on to something else.

But is that your highest truth?

I call creative apathy a smokescreen because it tricks you into thinking you’ve lost interest. It obscures the fact that you’ve encountered resistance to your project. It sends you off on a tangent, looking for other projects, wondering why you’ve lost interest, thinking maybe you never should have picked the project in the first place.

In my experience working with writers this creative apathy usually comes up as a response to either fear or creative burnout. The latter, creative burnout, comes about from pushing ourselves too hard or too long and becoming creatively exhausted. The former, fear, happens when we bump up against the places in our writing where we feel uncomfortable.

This fear could be as simple as being afraid to do the hard work, not knowing what comes next, or not knowing how to solve a story problem. It can be triggered by not having enough information about how to proceed with a task.

The fear can also arise from beliefs about your ability and talent, like a belief you should already know exactly how to do something before you even try.

I find that many, many writers hold this idea that writing should come naturally. That it should be easy, and that if it isn’t, it is a matter of a lack of talent or ability.

Carol Dweck, in her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success*, suggests that this belief demonstrates a “fixed mindset” – that we have everything we are capable of having from birth, that we cannot improve or increase our skills, etc. She contrasts this with a “growth mindset”, which says that we are capable of more if we focus on learning and applying ourselves.

I was struck by this comment she made:

“People are all born with a love of learning, but the fixed mindset can undo it. Think of a time you were enjoying something – doing a crossword puzzle, playing a sport, learning a new dance. Then it became hard and you wanted out. Maybe you suddenly felt tired, dizzy, bored, or hungry. Next time this happens, don’t fool yourself. It’s the fixed mindset. Put yourself in a growth mindset. Picture your brain forming new connections as you meet the challenge and learn. Keep on going.”

What if the next time you feel bored with a project, you consider the possibility that fear is coming up and sending you into a fixed mindset place – the very opposite of creativity – and instead choose to believe that you are capable of solving whatever problem you’re avoiding, even if it means getting help, brainstorming longer, or doing research to help you tackle it?

In other words, what if you adopted a perspective that said, “I can do this, somehow, even if I can’t see how yet“?

Perhaps it helps to also hold the belief that if you conceived of the project, you are also capable of seeing it through.

Your turn

Do you fall for creative apathy or forge through it? What’s your approach? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Warmly,

You may also be interested in:

* Affiliate link

by Jenna | Aug 28, 2013 | Writing Articles

In my writing community, one of the things writers commonly bring up as a question is how to reward themselves for meeting their writing goals.

We have a list of questions we answer on our site, once we’ve completed our writing for the day (or not, as the case may be). This is one of the stickiest questions for many of us:

- How will you acknowledge or celebrate what you’ve accomplished today?

The question tends to trigger a lot of resistance and debate and discussion. Sometimes writers even avoid answering it or fulfilling it. I know it’s a hard one for me to remember too!

But here’s the thing, it’s incredibly important to both celebrate and acknowledge the work you do as a writer both on an ongoing daily basis and at the end of a significant project phase, like finishing a first draft or a rewrite.

Here’s why:

- You’ve fought resistance to show up, put your butt in your seat, and do the writing. As small as that may seem from the outside, you know deep down that every day it is an accomplishment. We’re talking about a daily battle that you’re winning.

- By creating a positive association with your writing, you are more likely to show up and do it again the next day. Bottom line? It reinforces your writing habit.

- Writing is a long term endeavor. It’s all too easy to walk around feeling like you’ve never done enough when the draft isn’t finished. Stop that right now. Instead, celebrate what you have done. It’ll make it easier to keep going all the way through to the end.

- Too many writers significantly undervalue themselves and their writing, especially if the day’s writing session was particularly hard. Stop that too. Take the time to recognize the value and importance of what you’re doing. It’s important to you, right? For most of us, writing is a true calling. If that isn’t important to feed, honor, and sustain, I don’t know what is.

Ideas for rewards

Here are some super simple ideas to get you started with rewards, celebrations, and acknowledgments:

- Do a happy dance.

- Dance to music for a minute.

- Shout, “I did it!”

- Throw your fists up in the air and say, “YES!”

- Say, “I declare myself satisfied!”

- Hug yourself.

- Pat yourself on the back.

- Play an inspiring song.

- Make yourself a cup of tea.

- Take a moment to stretch.

- Stand in the sunshine for a moment, look at the sky and appreciate the world and the gift of writing.

- Do the things you’d normally be doing while procrastinating about your writing (like checking in on Facebook or Twitter, or playing games on your iPad).

- Tell your writing community about your progress and be proud of yourself.

Two tips for getting the most out of rewards

- Tip #1: B.J.Fogg of https://tinyhabits.com recommends celebrating within a second of completing the task as being critical for reinforcing small successes. So even if you give yourself a bigger reward at the end of the day’s work, do mini-celebrations each time you hit a milestone (e.g. a page done, a hour of writing, 15 minutes of writing, whatever you’re aiming for). I have a sound effect for a cheering crowd set up on my iPhone that goes off whenever I finish an hour-long writing sprint. It always reminds me to notice and acknowledge what I’ve accomplished.

- Tip #2: Don’t “pre-celebrate.” Pre-celebrating means doing something fun — celebrating or rewarding yourself — BEFORE you do the writing. That doesn’t work, because it only perpetuates procrastination AND triggers a guilty conscience. The whole idea here is to eliminate your guilt and anxiety around your writing.

But what about the major milestones?

What happens when you finish your draft, put the final polish on your rewrite, turn in your script to a contest, or your box of books arrives in the mail — in other words, hit a major writing milestone?

Please — and you may take this as a request from your writing coach if you like — REALLY celebrate!

Do something like this:

- Take yourself out to a fantastic lunch or dinner.

- Go to the spa for the day.

- Take a day off and watch movies and eat your favorite foods.

- Open a bottle of something yummy.

- Tell your friends.

- Have a party!

This is a MAJOR accomplishment and deserves to be celebrated.

Particularly if you’re someone who tends to undervalue and underrate and always have more to do and feel like you have to move on to the next thing, STOP, and congratulate yourself on finishing.

Then dive back in the next day. :)

You may also be interested in:

Image by © Royalty-Free/Corbis

In the third and final session of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "Bridging the Gap from Motivation to Structure With the Enneagram." Today's post is a recap of what we discussed.

In the third and final session of my interview series with Enneagram and story development expert Jeff Lyons (recordings no longer available), we talked about "Bridging the Gap from Motivation to Structure With the Enneagram." Today's post is a recap of what we discussed.![]()